Purpose

- Investigates the causes of economic imbalances.

- Investigates the effect of the global financial system and/or the monetary system in fostering a sustainable economy.

- Investigates causes tending to destroy or impair the free-market system.

- Explores and develops market-based solutions.

Summary

Tourism and recreation, freshwater and fisheries are examples of ecosystem services which, due to inappropriate or non-existent pricing mechanisms are eroding the natural capital on which they depend. The resulting economic imbalance in the monetary system undermines the functioning of the free-market system such that the long-term provision of these essential societal services and the well-being of the people who depend upon them is threatened. This project proposes to address this economic imbalance by carrying out studies to place an economic value on ecosystem services and to develop market-based mechanisms and policy recommendations to facilitate the establishment of environmentally and financially sustainable pricing practices for ecosystem services at park systems in some of the most ecologically important regions of the world.

Angel Falls, Canaima National Park (photo by Andy Drumm)

Description

Introduction

We are pleased to share with the Alex C. Walker Foundation this report describing the post-2007 advances enabled — and inspired — by your generous gift to the Conservancy. The initiative you funded aimed to carry out studies that would assign an economic value to ecosystem services, developing market-based mechanisms and policy recommendations to facilitate establishment of environmentally and financially sustainable pricing practices for ecosystem services at park systems in some of the most ecologically important regions of the world. In the context of a broad international alliance that included the Foundation, UNESCO, USAID and the U.S. National Park Service, we sought to promote an enabling environment for a free-market solution to this problem; an environment benefitting conservation, community and business.

During the compilation of this report — a process during which input was solicited from many leadership and field personnel across the Conservancy’s Latin American Region — one message was heard early and often: Even though the Foundation’s funding did not directly support many of the ecotourism-related projects that have been developing during the past three years, the accomplishments of these projects, their leaders tell us, are directly traceable to the catalyzing advances made possible by the Foundation’s early commitment to the cause.

These advances listed in this report, therefore, are of two varieties:

o The achievements directly enabled by your funds since 2007, including those in:

? -- Bolivia’s Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, where your funding supported site visits and studies regarding tourism concession models for the Park, fueling the subsequent UNESCO initiative there.

? -- Brazil’s Parana State: where a Conservation Action Plan (CAP) has been carried out

o Advances directly attributable to the catalytic leadership of the Alex C. Walker Foundation, including:

? -- Ecuador: formation and subsequent accomplishments of the Global Sustainable Tourism Alliance (GSTA),

? --Colombia: a recent assessment of the concession of tourism services in the private sector at two National Natural Parks, Gorgona Island and Tayrona, and development of a Marine Protected Area in National Park Corales del Rosario and San Bernardo where we are helping to design standards for sustainable marine tourism, and

? Latin American field staff applauds the effect of the Foundation’s grant in informing the Conservancy’s work with UNESCO, as exemplified by advances in Venezuela’s Canaima National Park.

It should be appreciated that the advances in this latter category represent achievements that are aligned with the goals of the original Alex C, Walker Foundation’s grant to the Nature Conservancy: to achieve sensible, sustained valuation of ecosystem services and the establishment of sustainable funding mechanisms for them.

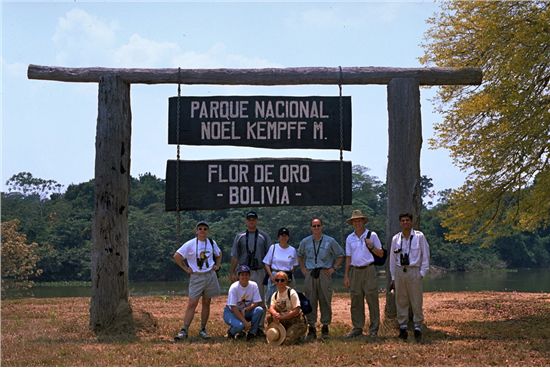

A group of ecotourists in front of sign at Flor de Oro in Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Bolivia © The Nature Conservancy

Purpose

The studies carried out in Ecuador, Peru and across South America have established a new approach to account financially for the economic value of the tourism and recereation function of ecosystem services provided by natural capital in protected areas. This directly addresses the prevailing economic imbalances associated with natural resource management. It is now impacting policy making in those countries and contributing measurably to the development of market-based approaches to managing tourism and recreation as governments realise the potential and importance of developing tourism concession frameworks, facilitating private investment and an expansion of the free market system to include parks and the management of natural capital.

Scope

Bolivia: Noel Kempff Mercado National Park

Noel Kempff Mercado National Park is one of the largest (3,763,414 acres) and most intact parks in the Amazon Basin. With an altitudinal range of 200 m to nearly 1,000 m, it is the site of a rich mosaic of habitat types from Cerrado savannah and forest to upland evergreen Amazonian forests. The park boasts an evolutionary history dating back over a billion years to the Precambrian period. An estimated 4,000 species of flora as well as over 600 bird species and viable populations of many globally endangered or threatened vertebrate species live in the park. Noel Kempff is one of the Conservancy’s worldwide demonstration sites for our REDD+ (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) work.

Funding from the Alex C. Walker Foundation was used to support site visits and studies about the concession models for the park, and the results then used to design and shape the subsequent UNESCO project.

A visitor center was constructed with the aim of fostering income generation through tourism activities, which would work in combination with the project endowment to fund post-project activities. Cabins were built and repaired in several communities, boats and equipment purchased, and a pontoon bridge constructed for vehicle transportation. Two communities participated in tourism activities by offering guidance, lodging, and other services. Unfortunately, it became apparent that the remote location of NK-CAP would make travel to the site by tourists both difficult and expensive. Thus, the realized benefits via ecotourism have been fewer than originally anticipated.

That said, it should be noted that the study, the studies relating to Noel Kempff that were funded by the Foundation catalyzed/informed financing mechanisms that have subsequently been developed in the following locations in Bolivia: (1)user fees are charged in the National Eduardo Avaroa Flora and Fauna Reserve (Andean puna ecosystem); (2) Amboró National Park, Comarapa Municipality, where user fees are charged for water services provided to the Municipality by the Los Negros community; and (3) Madidi National Park, where user fees are now charged.

Brazil, Parana State, Guaratuba Bay

Guaratuba Bay is a very productive system with a large extension of mangroves and a large oyster population. In 2007, this bay was selected by the Conservancy’s Coastal and Marine Conservation Program in South America Priority as a priority site for biodiversity conservation in Brazil.

With the support of the Alex C. Walker Foundation, the Conservancy and Grupo Integrado de Aquacultura e Ambiente (GIA) formed a partnership with the NGO 5 Reinos to carry out Conservation Action Planning (CAP) in the Guaratuba Bay. Owing to its considerable experience in planning methodology, 5 Reinos was chosen to lead the CAP, and its director, with support from the Conservancy, joined our “CAP Coaches network” and attended the Coaches Rally annual meeting in 2007, in Oregon. 5 Reinos has, subsequently, been leading other CAPs across Brazil.

The Conservation Action Planning process in Guaratuba Bay involved local stakeholders, including the university, the local community and multiple decision makers. Several interviews, meetings and workshops were conduced to ensure the active participation of these stakeholders.

The conservation targets selected included fish, shrimp, mangroves, estuaries and freshwater inflows to estuaries. A social target was also selected: the local fishermen. Conservation threats were classified according to their scope and severity, with the largest threats being overfishing, illegal fishing, lack of organization for the use of the marine landscape, loss of cultural identity and a shortfall in social organization among fishermen and local communities. The optimal strategies to abate these threats were also selected:

o promote landscape planning and resources use with the social participation,

o identify and support key academic researcher to support this planning,

o promote and coordinate local tourism,

o increase the capacity and improve the local swage system, and

o improve the monitoring system.

The results of the Walker-Foundation-supported Conservation Action Planning endeavor are being used to support the State Environmental Secretary planning and are incorporated in to the management plan of the Guaratuba Bay Protect Area. It has also been used to support the local council to build a participatory planning process in the region.

Ecuador

Support from the Alex C. Walker Foundation was key to the formation of the Ecuador Global Sustainable Tourism Alliance (GSTA) project, which eventually produced many, ongoing accomplishments focusing on consolidation of seven Protected Areas:

o Corredor Ecoturístico Amazónico Yasuni Cuyabeno

o Reserva Ecológica Cotacachi Cayapas - Parte Alta

o Reserva Ecológica Manglares Churute

o Parque Nacional Cotopaxi

o Nacional Machalilla

o Reserva Faunística Chimborazo

o Reserva Ecológica Cayambe Coca (Papallacta-San Rafael-Chaco-Oyacachi Circuit)

Within these Protected Areas, resources totaling more than $2.5M — from USAID and from funds mobilized by the Conservancy – are supporting stakeholder actions to promote tourism development and expansion in the following five broad areas:

1) Improving the national tourism and protected area policy environments: To position Ecuador and its protected areas as major sustainable travel destinations by creating a transparent system for investors and visitors

2) Developing demand-driven products and services and promote investments: To develop and position a protected area’s brand with an array of high quality tourism products and services

3) Building capable and competent institutions, services, and personnel: To enhance the skills of the public sector, private sector, and local communities at the protected areas system and site levels

4) Stimulating innovation and replication of tourism products and services: To identify opportunities for innovation and rapid sharing of new technologies and services through emerging networks

5) Monitoring and evaluating program performance: To provide timely data to facilitate corrective action, validate assumptions, and verify program impact Main results of the Ecuadorian Alliance's project for sustainable tourism.

Specific, relevant accomplishments of the Conservancy’s Ecuador Country Program include:

1) Development of the foundation for the design and implementation of the Program of Tourism for the Heritage Natural Areas of Ecuador

The Protected Area Tourism Program designed by the project has been accepted by the Ministry of Environment (MAE). In this program there is a major component of financial sustainability, which is incorporating all the work done previously in studies of financing needs, and economic valuation of Tourism. The implementation of this program starts with resources allocated by the government this year, and will generate more income for Protected Areas. In 2009, The MAE infused 2.5 million to begin implementation.

2) Improvement of tourism infrastructure in 4 Protected Areas:

?o Construction of Visitor Center El Arenal, Chimborazo Faunal Production Reserve.

?o Construction of Pier La Flora, Churute Mangrove Ecological Reserve

?o Improvement Laguna Limpiopungo Path, Cotopaxi National Park.

?o Oyacachi Path Design - El Chaco, Cayambe Coca Ecological Reserve.

3) Development of GIS for 7 Protected Areas with tourist attractions and facilities.

4) Design and Implementation of Management System of Tourism for 7 Protected Areas and based on Least Cost Management and Limits of Acceptable Change.The methodology was implemented in the Protected Areas, MAE staff was trained.

Columbia

During the past year, in Colombia, we carried out an assessment of the concession of tourism services to the private sector at two National Natural Parks: Gorgona Island and Tayrona. The assessment was the first one of this kind in the country and looked at the degree of environmental sustainability of tourism and how things have changed in terms of conservation in those protected areas since the scheme of tourism concessions began. The final documents from this assessment have just been presented to staff from Columbia’s National Parks Unit so that they can take management decisions accordingly.

The Conservancy is also currently working at a Caribbean Marine Protected Area (MPA) in Colombia (National Park Corales del Rosario and San Bernardo) where we are helping to design standards for sustainable marine tourism focusing on: establishing carrying capacity limits at key sites, monitoring and reducing the ecological impacts of tourism activities/infrastructure and ensuring the viability of conservation targets. The final result will be a Tourism Management Plan for the Protected Area that we expect to have ready by the end of 2010. These projects have used funds from the North American Sustainable Consumption Alliance’s (NASCA´s) Protected Areas Strategy.

Venezuela: Canaima National Park

In 2007, the Conservancy and the UNESCO World Heritage Centre forged a partnership in 2007 to engage the tourism sector in support of conservation in World Heritage sites around the world. The project aims to provide planning and business skills development for site managers, help train local entrepreneurs to strengthen and promote local products, develop creative approaches to use tourism to assist site conservation financing, and work with the tourism industry to address key tourism-related challenges and issues at World Heritage sites.

Canaima National Park was among five pilot sites worldwide chosen to implement this groundbreaking work. Over the past three years with UNESCO’s support in particular, we have been able to more proactively forge positive relationships between local communities, tourism operators and government towards a common vision for the park’s management and tourism. The Conservancy considers the work in Canaima National Park vital for the overall conservation of Venezuela’s Amazon region and a potential model for other parks and World Heritage sites. Accomplishments include:

1) Working group created to strengthen co-management of Canaima National Park. The group is part of the effort to strengthen co-management of the park between the Pemón and park authorities, The Conservancy helped create a tourism working group to make recommendations to the sustainable use plan for the park’s Western section of the park, a three-million acre section that has been highly impacted by tourism. In coming months, we will continue to build relationships between the Pemón, park management, regional tourism agencies, local tourism operators, and other important actors.

2 )Facilitating collaborative management agreements between the Pemón and local tourism operators. Establishing a common vision for tourism is important for the long-term conservation and management of Canaima National Park and sustaining the livelihoods of the people who live in it. Over the life of the project, Pemón leaders, their representative indigenous organizations, and local tourism operators united to discuss the possibility of establishing agreements to jointly implement tourism activities and minimize their environmental impacts. For example, local leaders from the Kanaimö sector of the park engaged with four local tourism operators to define objectives to jointly cooperate in the Laguna area of the park. Over the coming months, we will continue to help outline common objectives and forge agreements between communities and these and possibly other local tourism operators.

3) Canaima park entrance fee is increased. Since 2004, the Conservancy has been supporting the Pemón to conduct long-term planning of natural resources in their territories towards a sustainable future. As a result of this dialogue, the Pemón agreed that the park entrance fee was too low and proposed an increase to the government, which was later accepted. This past year the government increased the

park entrance fee from the U.S. dollar equivalent of $3 to $15--a five-fold increase. An estimated 80 percent of the entrance fee will be directed to Canaima community to assist with school and community upkeep. This entrance fee increase is important as it will help increase communities’ incentive to protect the park by receiving greater benefits from its conservation as a world-class tourism destination.

4) Bilingual manual created for environmental education and ecotourism. With our support, local partners and the Agroecology and Ecotourism School in the Kanaimö sector of Canaima created a manual to assist local indigenous students at the school and community members with bilingual environmental education and ecotourism activities. The first of its kind, the material outlines norms and procedures for guiding tourism management, something in which the school’s students and professors primarily work. This manual also documents the joint objectives agreed upon between local operators and communities for this sector of the park.

5) Book launched on the future of biodiversity conservation in Pemón territories. With support from FFEM, in 2008 the Conservancy and partners launched an important publication that documents the on-going process of natural resource planning and conservation in Pemón territories, which encompass Canaima National Park. This book presents the vision and future of the Pemón for their traditional lands. Among others, the communities identified community-based tourism is as a source of economic potential, and the need for additional training in tourism management and development as a priority. In response, the Conservancy will continue to help build the capacity of local indigenous groups in tourism and natural resource management as a means of strengthening co-management in the park.

Conclusion

The Nature Conservancy hopes that the Alex C. Walker Foundation will be gratified by the quite remarkable range of advances its funding and its influence has achieved across Latin America. The accomplishments the Foundation’s funding yielded since 2007 have had important regional impacts. And, as remarked earlier, a common refrain from our field staff in Latin America was that “although the Foundation didn’t fund this particular project, our work was informed and strengthened by the leadership work it did support.” Catalytic results of this nature are certainly a testament to our conservation staff’s dedication, but they are also, more fundamentally, the results of the generosity of a perspicacious donor.

We thank you for your support, and look forward to our ongoing partnership.

Amount Approved$90,000.00

on 11/7/2006

(Check sent: 11/29/2006)

Parks Congress at Bariloche, Argentina where Andy Drumm of The Nature Conservancy presented preliminary results for a Walker Foundation funded study of user-fee funding of parks.