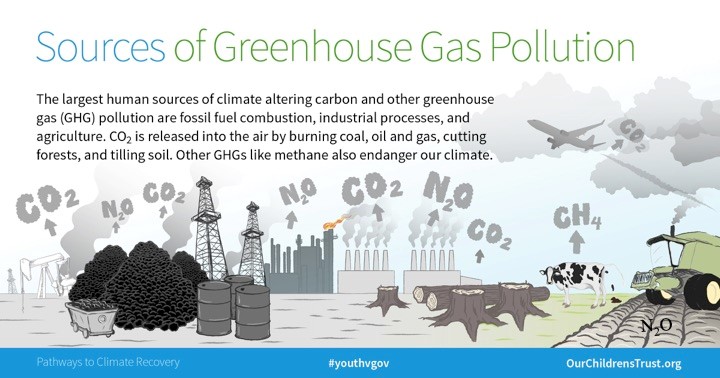

Despite its small size, the Walker Foundation is seeking big change. The conflict between political ideology and scientific and economic facts about climate change are at the point of locking in irreparable harm. The Foundation has taken bold steps by funding projects designed to address global warming and ocean acidification. Additional climate grants focus on two areas. First support efforts to keep ecosystems, such as coral reefs, alive while climate threats are addressed. And second, support studies of how coal miners, and communities dependent on fossil fuels, can transition to a more sustainable future. Fossil fuels power our economy.

Fossil fuels are cheap and abundant sources of concentrated energy. Despite the economic advantages of fossil fuels, scientists have long recognized the potential for the burning of fossil fuels to alter earth’s atmosphere, raise global temperatures, and acidify the oceans.

Illustrations accompanying this article credited to Our Children’s Trust, were created through a Walker Foundation grant. The group’s goal is to secure the legal right to a healthy atmosphere and stable climate. Other illustrations are separately credited.

Illustrations accompanying this article credited to Our Children’s Trust, were created through a Walker Foundation grant. The group’s goal is to secure the legal right to a healthy atmosphere and stable climate. Other illustrations are separately credited.

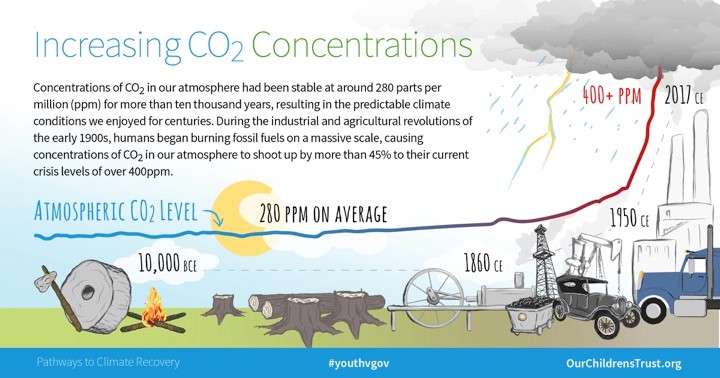

Beginning with the International Geophysical Year in 1957, stations were established to consistently measure gases in the atmosphere over time. The measurements soon revealed the level of carbon dioxide was increasing at an accelerating rate. Oceans, forests, and other ecosystems absorb about half the carbon dioxide released by human activity. The other half accumulates in the atmosphere raising global temperatures.

1

Fifty years ago President Lyndon Johnson’s science advisory committee sent him a report warning that “Man is unwittingly conducting a vast geological experiment…burning fossil fuels that slowly accumulated in the earth over the past 500 million years”. The report warned that rising levels of carbon dioxide would warm the climate and predicted dire consequences.

2 By the1980’s scientific understanding of the risks posed by continued fossil fuel emissions brought world leaders close to a binding agreement addressing climate change.

3 Since then repeated efforts to curb emissions have failed, even though the costs of climate damage and ocean acidification are now beginning to impact the economy.

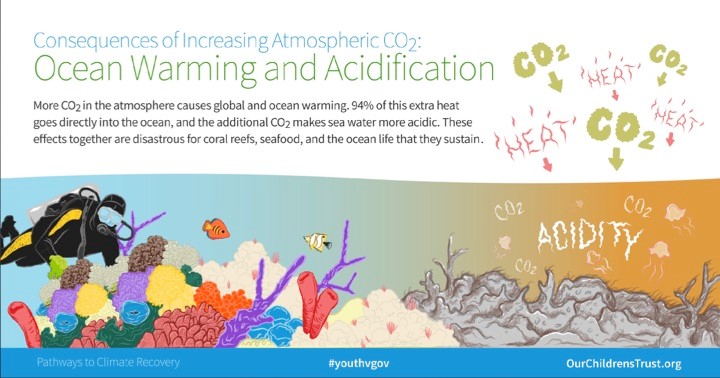

Carbon dioxide absorbed by the oceans makes the water more acidic, harming marine life. Seventy percent of the earth’s surface is covered by oceans, but what lies below is mostly out of sight. The Foundation director, Barrett Walker, is a diver and has seen first-hand the dramatic decline in the health of ocean ecosystems over the last 50 years. As a result of his concern, the Foundation funded a study by the Center for Sustainable Economy on the economic toll of ocean acidification and warming. This is the first study we know of that puts a price on damage to ocean ecosystems. The cost is staggering: unless prompt action is taken to dramatically reduce greenhouse emissions, global costs could top $20 Trillion a year by 2100.

4

The Walker Foundation has funded projects designed to slow the loss of ecosystems with the hope that fossil fuel emissions will be reduced in time to avoid a mass extinction. Beginning in 2012 we funded coral restoration by the Coral Restoration Foundation in South Florida. In an effort to demonstrate that coral restoration could be scaled up, we concentrated funding on reef restoration on the Caribbean Island of Bonaire, by partnering with the Island’s marine national park and dive resorts that charged user fees to help fund reef recovery. Half the island’s income is generated through ecotourism.

A 2017 film “Chasing Coral” visually documents the death of coral reefs around the world. Just as a slight rise in body temperature can quickly kill a human, warming ocean temperatures are wiping out coral reefs around the world.

5

With a great deal of effort, two species of branching coral, carefully collected in the wild, were propagated in nurseries and attached to frames anchored in the sand bottom. The out-planted coral was then cleaned of algae and parasitic worms and snails until it gradually grew large enough to survive without regular care. Although reported to be a great success, the Trustees reluctantly conclude that this and other restoration projects are likely to be temporary. The restored coral is not as diverse, does not cover as large an area, and is not as resilient as the original reefs. So success has to be tempered with the realization that with great human effort the coral is growing, but not flourishing, and is unlikely to survive for long if we don’t curtail fossil fuel emissions causing ocean warming and acidification.

In reality this is a simplified description of what is required to restore an ecosystem in decline. Real restoration requires recovery of fish populations, recovery of animals that graze algae, and recovery on a very large scale because coral is mass spawning.

Coral restoration in Bonaire funded by Walker Foundation Grants. On the left is a healthy coral reef supporting abundant fish life. Center, diver inspecting coral being grown in a nursery. The white bottom of the coral nursery was once completely covered by coral that died out, and was ground into sand by storms. Right, divers from the Coral Restoration Foundation swimming over a stand of restored coral out-planted from the nursery. There are now several large coral nurseries in Bonaire funded by resorts and large grants from the European Union. Photos by Barrett Walker.

Coral restoration in Bonaire funded by Walker Foundation Grants. On the left is a healthy coral reef supporting abundant fish life. Center, diver inspecting coral being grown in a nursery. The white bottom of the coral nursery was once completely covered by coral that died out, and was ground into sand by storms. Right, divers from the Coral Restoration Foundation swimming over a stand of restored coral out-planted from the nursery. There are now several large coral nurseries in Bonaire funded by resorts and large grants from the European Union. Photos by Barrett Walker.

Our founder, Alex C. Walker, lived through the Great Depression in the 1930s. The human suffering and loss of wealth resulting from this decade-long economic downturn was undoubtedly one of the events that led Alex to establish the Foundation. The first purpose that Alex describes in his will is to investigate the causes of economic imbalances, such as recessions and depressions. The current trustees are honoring our donor’s intent by making climate change a major focus of Foundation grants.

Climate change threatens a decline in the economy far more damaging than the Great Depression. After leaving office, Republican Treasury Secretary, Henry Paulson, wrote an opinion article titled “The Coming Climate Crash”. He pointed out that by allowing excesses to build up in financial markets for many years, the result was the devastating financial crash of 2008, and “As a result millions of people suffered.” He warned: “We’re making the same mistake today with climate change. We’re staring down a climate bubble that poses enormous risks to both our environment and economy. The warning signs are clear and growing more urgent as the risks go unchecked.”

6

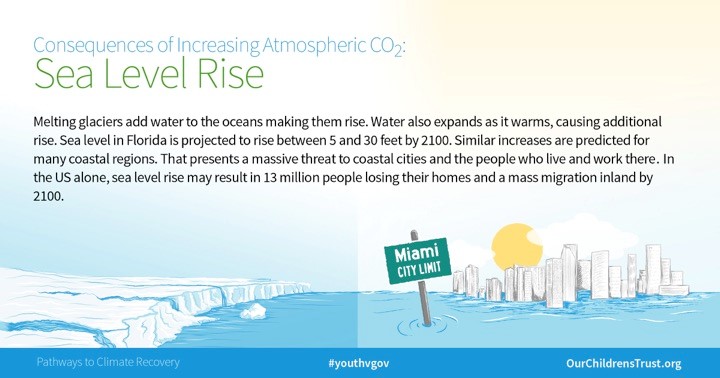

Foundation director, Barrett Walker, made a number of personal trips around the world confirming climate impacts reported by scientists. The loss of coral reefs, and melting of glaciers are two of the most dramatic but little-seen effects occurring today. Meltwater from land-based glaciers is contributing to sea-level rise and flooding of coastal cities. The result will be increasingly expensive mitigation measures, followed by abandonment of coastal real estate.

Retreat of the largest glacier in South America. The ice field of the Upsala Glacier in Patagonia lies in disputed territory between Argentina and Chile. The glacier is named for Uppsala University in Sweden that sponsored studies documenting retreat of ice. As land-based Glaciers around the world retreat, the meltwater contributes to sea level rise, and further accelerating global warming. When ice melts, the exposed land absorbs more heat than reflective ice, further accelerating sea level rise and additional melting in a vicious cycle. On a personal note: when photographing this scene from a mountaintop, Barrett remarked “Ice that once extended from horizon to horizon, has now retreated to a distant remnant”.

Retreat of the largest glacier in South America. The ice field of the Upsala Glacier in Patagonia lies in disputed territory between Argentina and Chile. The glacier is named for Uppsala University in Sweden that sponsored studies documenting retreat of ice. As land-based Glaciers around the world retreat, the meltwater contributes to sea level rise, and further accelerating global warming. When ice melts, the exposed land absorbs more heat than reflective ice, further accelerating sea level rise and additional melting in a vicious cycle. On a personal note: when photographing this scene from a mountaintop, Barrett remarked “Ice that once extended from horizon to horizon, has now retreated to a distant remnant”.

Although melting glaciers in far-away places may seem like a distant threat, resulting sea-sea-level rise is already flooding coastal cities here in the United States. These homes in North Carolina were torn down soon after being photographed, so a vacation visitor, or beach-front buyer, would likely be unaware of the ongoing loss of coastal real estate. Photos by Barrett Walker.

Markets Are Responding to Climate Risks

Although melting glaciers in far-away places may seem like a distant threat, resulting sea-sea-level rise is already flooding coastal cities here in the United States. These homes in North Carolina were torn down soon after being photographed, so a vacation visitor, or beach-front buyer, would likely be unaware of the ongoing loss of coastal real estate. Photos by Barrett Walker.

Markets Are Responding to Climate Risks

Markets are responding to climate costs. Take sea level rise as an example. The market response has been a decline in the price of homes exposed to sea level rise relative to comparable unexposed properties near the beach.

7 8 However, the true cost is hidden from consumers by subsidized flood Insurance. The National Flood Insurance Program was created by Congress in 1968 when private insurers withdrew from the market due to increasing losses. This subsidized federal program has been criticized for allowing development of coastal properties and flood plains. Although originally intended to protect floodplains and safeguard wetland species, the result has been the opposite because subsidized insurance encourages building and redevelopment of floodprone property. A 2017 Congressional report found the program ran a deficit of 1.4 billion dollars in the prior year.

9 The conservative Heritage Foundation found the accumulated debt of the National Flood Insurance Program is “nearly $25 billion as a result of borrowing from the U.S. Treasury to cover damage claims”.

10

A second example of market response to climate risk is fire. As the climate warms, earlier snowmelt and higher temperatures are causing increased evaporation and a higher likelihood of drought, especially during summer. Wildfires in the western United States are on the rise. Between 1986 and 2003, wildfires occurred nearly four times as often, burned more than six times the land area, and lasted almost five times as long when compared to the period between 1970 and 1986.

11 The initial market response has been an increase in insurance rates, and in some areas home insurance is getting harder to find.

12 The conservative Wall Street Journal announced that “California’s largest utility was overwhelmed by rapid climatic changes as a prolonged drought dried out much of the state and decimated forests, dramatically increasing the risk of fire.” In Jan, 2019, the paper announced that PG&E was the first, but probably not the last climate-change bankruptcy.

13

A third example of market response to climate risk is extreme weather events. Foundation director, Barrett Walker provides this story from personal experience. “In 1977 our family moved from Pittsburgh to Houston where I accepted a faculty position at the Baylor College of Medicine. The economy was booming and opportunity beckoned. I realized the construction of roads and parking lots would lead to more runoff as natural wetlands were developed, so we chose our home on higher ground. Houston had no zoning laws to slow growth fueled by expansion of the fossil fuel industry. Two years after arriving, a strong thunderstorm flooded the medical center, where I worked, and much of the City. I worried that if a stronger storm hit, our home could flood, and the region’s oildependent economy could crash. So we sold our house and moved. Soon after leaving in 1980, Houston suffered an economic downturn, but recovered. Despite repeated floods, most Houston residents rebuilt, continuing to believe storms were rare events, or bad luck, rather than a change in the climate. Perceptions changed with Hurricane Harvey.”

Photos: Left Barrett Walker, Houston medical center flood 1979; Center, U.S Air National Guard assists citizens impacted by Hurricane Harvey rainfall in Texas, photo by Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, 2017; Right, Port Arthur, TX, by Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, 2017.

Photos: Left Barrett Walker, Houston medical center flood 1979; Center, U.S Air National Guard assists citizens impacted by Hurricane Harvey rainfall in Texas, photo by Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, 2017; Right, Port Arthur, TX, by Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, 2017.

Sculpture by Atelier Van Lieshout in Rotterdam. Eighteen stacked oil drums evoke the promise and risks of fossil fuels. From the drums drips a syrupy mass in which one can make out human figures. As the energy hub of Europe, oil storage and transport helped fund Rotterdam’s recovery after WWII, but fossil fuel emissions caused the City to spend well over a billion dollars for flood gates and seawalls to protect against rising seas.

Sculpture by Atelier Van Lieshout in Rotterdam. Eighteen stacked oil drums evoke the promise and risks of fossil fuels. From the drums drips a syrupy mass in which one can make out human figures. As the energy hub of Europe, oil storage and transport helped fund Rotterdam’s recovery after WWII, but fossil fuel emissions caused the City to spend well over a billion dollars for flood gates and seawalls to protect against rising seas.

Hurricane Harvey had considerable economic impact. At its peak on Sept 1, 2017, one-third of Houston was underwater. 240,000 homes were damaged, three/fourths outside the 100 year flood plain. In the Gulf area, one million vehicles were ruined beyond repair. Harvey flooded 800 wastewater treatment facilities and 12 Superfund sites spreading sewage and toxic chemicals.

14 Harvey also dealt a blow to Gulf oil & gas infrastructure, with the greatest damage to refineries in Beaumont, Port Arthur and Corpus Christi.

The Five Costliest U.S. Hurricanes on Record - data from NOAA

Katrina …… 2005 ……..$161 Billion

Harvey …….2017 ……. $125 Billion

Maria …….. 2017 ……… 90 Billion

Sandy ……. 2012 …….. 71 Billion

Irma ……… 2017 ……… 50 Billion

Scientific certainty that atmospheric heating is caused by humans has now reached 99.9999%. In other words, there is less than a one-in-a-million chance that warming is not caused by fossil fuel emissions and the loss of natural ecosystems.

15 16

With so much real estate at risk from climate change, why aren’t big banks and financial institutions taking a more active role in minimizing that risk? A Federal Reserve policy paper argues that “…the anticipation of bailouts creates incentives for banks to herd in the sense of making similar investments. This herding behavior makes bailouts more likely and potential crises more severe.” 17 During the real estate collapse of 2008, the federal government bailed out banks with risky loans by passing the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Although it can be argued that the TARP bank bailout avoided a far worse financial collapse, the program emboldened banks to accept more risk, knowing that the government was likely to bail them out if they faced missive default. With 40% of the nation’s population living in counties directly on the shoreline, and with growth concentrated along the coasts, banks continue to make loans, even though climate risk increases the probability of massive default.

Although coastal real estate prices have declined by ten percent,

why aren’t more individual homeowners responding to climate risk by moving away from flood-prone areas? Foundation director, Barrett Walker, regularly travels to the coast. He’s found that public officials and residents of coastal communities minimize talking publicly about climate risk for fear of scarring away potential home buyers. Depending on the area, the average 30 year mortgage only has a life of 3 - 7 years. So homeowners have a very short investment horizon, and their individual risk is minimized by National Flood Insurance. Because the National Flood Insurance Program operates through deficit financing, today's climate risk burden is transferred to future U.S. taxpayers.

- Earth still absorbing about half carbon dioxide emissions produced by people: study, NOAA in phys.org, Aug 1, 2012.

- Reference to 1965 White House Document “Restoring the Qulaity of Our Environment” in Skeptical Science, by Glenn Tamblyn, Feb 18, 2015.

- Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change, by Nathaniel Rich, photos by George Steinmetz, The New York Times Magazine, Aug. 1, 2018.

- Ocean Acidification and Warming: The economic toll and implications for the social cost of carbon, John Talberth and Ernie Niemi, Center for Sustainable Economy, Nature Climate Change 2, 146-147, 2012.

- Chasing Coral Documentary Film.

- The Coming Climate Crash, Henry M. Paulson, Jr., The New York Times, June 21, 2014.

- Disaster on the Horizon: The Price Effect of Sea Level Rise, Asaf Bernstein, Matthew Gustafson, Ryan Lewis, Journal of Financial Economics, Jul, 26, 2018.

- Rising Sea Levels Reshape Miami’s Housing Market, Laura Kusito and Arian Campo-Flores, Wall Street Journal, April, 20, 2018.

- The National Flood Insurance Program: Financial Soundness and Affordability, Congressional Budget Office, Sept. 1, 2017.

- The National Flood Insurance Program: Drowning in Debt and Due for Phase-out, Diane Katz, The Heritage Foundation, June 22, 2017.

- Is Global Warming Fueling Increased Wildfire Risks? Union of Concerned Scientists.

- As Wildfire Risk Increases, Home Insurance Is Harder to Find, by Sophie Quinton, Pew Charitable Trusts, Jan. 3, 2019.

- PG&E: The First Climate-Change Bankruptcy, Probably Not the Last, by Russell Gold, Wall Street Journal, Jan. 18, 2019.

- Hurricane Harvey Facts, Damage and Costs, by Kimberly Amadeo, The Balance, updated Jan. 20, 2019.

- Scientists Say Evidence for Man-Made Climate Change Has Reached a 'Gold Standard' of Certainty, by Eric Sherman, Fortune, Feb, 26, 2019.

- Celebrating the anniversary of three key events in climate change science, Benjamin D. Santer et. al., Nature Climate Change Vol. 9, March 2019.

- Too Correlated to Fail, by V.V. Chari and Christopher Phelan, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, July, 22 2014.

Previous Next